It is my considered opinion that it’s good to be the King. Much better than not being the King. I spent the first five years of my life not being the King, and it sucked. Then I became the King, and all was well. King of what, you may ask? All. Of. It.

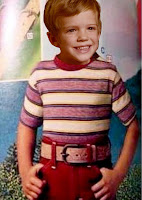

Although you wouldn’t know it to look at me now, parts of my

life were spent not being totally awesome at all times. In fact, I grew up

wearing Toughskins jeans, Pro-Wings tennis shoes, and various other house-brand

garments from Zodys, K-Mart, and Monkey-Wards. My parents probably thought I didn’t know the difference between Izod Lacoste and Sears' Braggin’ Dragon, but

I did. Oh, yes I did.

Although you wouldn’t know it to look at me now, parts of my

life were spent not being totally awesome at all times. In fact, I grew up

wearing Toughskins jeans, Pro-Wings tennis shoes, and various other house-brand

garments from Zodys, K-Mart, and Monkey-Wards. My parents probably thought I didn’t know the difference between Izod Lacoste and Sears' Braggin’ Dragon, but

I did. Oh, yes I did.

Of course, I wasn’t born knowing the difference, I had to be

taught. And who better to teach you to that there’s something wrong with you

than all the other kids? There you are,

just walking down the street secure in the knowledge that Mom and Dad

are doing right by you, only to discover that they let you out the door

thinkin' you ballin’, when in fact your Garanimal-clad ass is subject to

ridicule in those streets because of their dereliction. It’s child-abuse, really.

Apparently, real Vans have a distinctive waffle tread on the

bottom that the Payless version don’t have. Apparently, real Lego are not

interchangeable with Duplo blocks, Lincoln Logs do not play well with Frontier

Logs, and real Big-Wheels are not made of metal. All of which I discovered the

hard way. Walk outside all atwitter with the excitement of new stuff, only to

be met with derision in the street over something so nebulous as a stamp, a brand,

or a label on your stuff. How the hell anyone knew which one was the ‘right’

one was beyond me. But it was real easy to tell which was the wrong one, because it

was always whatever I had. What are the odds?

Of all the egregious counterfeits I ever tried to pass off

as ready for prime-time, nothing compared to my metal big-wheel. The popular (read: name-brand) Big-Wheel was a plastic dragster-style tricycle, with recumbent seating and flashy coloring. Mine was brown metal but had chopper-style handlebars on it, which I thought kicked-ass. It turned out that I was wrong about that. Additionally, being much heavier it didn’t have great off-the-line speed, since the inertia was tough for five-year-old legs to overcome. Meaning that not only was it drab, it was slow. So the length of time it took for me to go from excitement about my uniqueness to humiliation for the exact same reason was quicker than popping a Pop-Tart.

Of all the egregious counterfeits I ever tried to pass off

as ready for prime-time, nothing compared to my metal big-wheel. The popular (read: name-brand) Big-Wheel was a plastic dragster-style tricycle, with recumbent seating and flashy coloring. Mine was brown metal but had chopper-style handlebars on it, which I thought kicked-ass. It turned out that I was wrong about that. Additionally, being much heavier it didn’t have great off-the-line speed, since the inertia was tough for five-year-old legs to overcome. Meaning that not only was it drab, it was slow. So the length of time it took for me to go from excitement about my uniqueness to humiliation for the exact same reason was quicker than popping a Pop-Tart.  Once other children have deemed something worthy of mockery,

your otherwise beatified parents can offer no redemption. So their explanation of the

virtues of an indestructible big-wheel meant nothing to me, because durability

implies longevity and the spectrum of time. And as a kid there was no such

thing as later on, down the road, or in the long-run. All I had was right now,

and right now I didn’t fit in. Taking pity on me, my Dad took the big-wheel to

work with him at the Naval Base in Monterey. There he had a couple of

Mid-shipmen engineers disassemble and spray-paint it hot-rod purple, complete with

shiny metallic flakes, which would obviously make it much faster. It was so

badass.

Once other children have deemed something worthy of mockery,

your otherwise beatified parents can offer no redemption. So their explanation of the

virtues of an indestructible big-wheel meant nothing to me, because durability

implies longevity and the spectrum of time. And as a kid there was no such

thing as later on, down the road, or in the long-run. All I had was right now,

and right now I didn’t fit in. Taking pity on me, my Dad took the big-wheel to

work with him at the Naval Base in Monterey. There he had a couple of

Mid-shipmen engineers disassemble and spray-paint it hot-rod purple, complete with

shiny metallic flakes, which would obviously make it much faster. It was so

badass.

Or it was, until I took it outside.

“Ha! Look at your gay big-wheel!” Bryan Verbrugge exclaimed from

astride his name-brand Big-Wheel. His twin brother Kevin was the first to join

in the chorus of laughter and pointing that spread quickly through the semi-circle

of other kids. “Ooooh, so shiny!” Kevin cooed, he with his hornet-like

Green-Machine—obviously someone that could never be uncool. I’d literally

never heard the word “gay,” but at first blush it didn't seem complimentary.

In that moment, I was filled with a hopeless certainty that

I could never escape the inherent unworthiness that seemed to attend my very

existence. Suddenly, this black rage boiled over in me and I fired up my gay big-wheel, setting a collision course. Do you have any idea what happens when forty-five pounds of five-year-old astride thirty pounds of steel hits ten pounds of an all-plastic Big-Wheel at full-tilt ramming-speed? The effect was spectacular; the suspension forks and that iconic front wheel folded like a pizza-box struck by a sledgehammer.

Both Bryan and I were equally shocked by the result,

although our reactions diverged immediately thereafter. He started to scream

bloody murder over his irreparably-mangled toy, while I was exultant with the

sudden, shocking recognition of the power I and my unique big-wheel possessed. But the exhilaration of my victory was short lived, because his

brother Kevin instantly yelled the two most terrifying words that a

five-year-old can hear: "I'm telling!" He flipped a quick one-eighty on his agile Green-Machine

and high-tailed it out of there. At first, I was worried that he was going to

my house to tell my folks, but when I realized he was headed home to tell his

own parents I was truly terrified. I took off after him post-haste, with no

plan other than to silence him.

With his head-start and the inertia of my heavier ride,

there was no way I could catch up to him. That didn’t stop me from pedaling pell-mell after him, as though my life depended on it. When we hit the downhill slope at the other end of Mervine St. near where he lived, something unexpected began to happen: my big-wheel started to pick up speed. Like, so much speed that my feet couldn’t stay on the furiously revolving pedals and were thrown clear, almost derailing my pursuit. Instead, I tucked them in on the bar between the seat and the suspension forks, gripped those chopper-handlebars for dear life, and let my gay big-wheel do its own thing. The greater weight of my shiny dragster on the downhill straightaway allowed me to overtake Kevin and his fancy plastic Green-Machine.

He looked back just in time to see me and my sparkly-purple steed bearing down on him. I

can only imagine the maniacal look I must’ve been wearing to inspire the terror written on his face. When my front tire drilled his

right rear tire he immediately spun out of control and crashed,

ass-over-teakettle. Like his twin's before him, Kevin's ride was permanently damaged as well, the plastic rear wheel

being badly dented, and thus the Green-Machine was never the same.

Eventually word got around to the parents that I was the one

destroying all the Big-Wheels in town, at which point my own parents attempted to

rein-in the reign of O’B The Terrible by teaching me to ride a bike instead.

But it was too late, I was on my path and I been ballin’ ever since.